Carrier Operations in Flightgear

Author: Thorsten Renk

Pre-flight preparation

The flight deck of the USS Carl Vinson, 8:30 am Pacific Daylight Time, off the US west coast: an F-14b is made ready for a flight. The weather is rough, 16 kt of winds coming from the open ocean, with gusts reaching up to 20 kt and changing directions. The Vinson has just crossed a patch of rain, but the clouds seem to be breaking up.

While the ground crew takes care of the plane, the pilot and the RIO go through mission briefing. Our flight this morning will be an intercept training – there is an intercept target north of us which we are to identify.

The scenario is set up using Flightgear’s AI system – both the carrier group and the intercept target are defined as AI scenarios which are defined before starting the simulation. Here I am using a simple setup placing a target on a predefined course – but using Flightgear’s scripting language, it would easily be possible to set up a situation completely unknown to me, or an unknown number of targets, or even a scenario which reacts to my presence in a certain way. AI scenarios can be quite complex – the Vinson scenario simulates the movement of a whole carrier group! The weather conditions can come from live weather reports, or be generated by a sophisticated offline weather system. Many planes in Flightgear (such as the F-14b) offer multi-crew support, i.e. in principle I could share this mission with a human as RIO – in this case however, I’m actually flying alone.

Ready to launch!

We enter the cockpit and close the canopy. While the crew arms the plane (we’ll be carrying a light air-superiority loadout), I am busy adjusting the plane for takeoff. Among other things, I adjust my altimeter to the current pressure and enter the TACAN channel of the Vinson into the left console. TACAN (TACtical Air Navigation) will be my guide back to the Vinson across a cloud-covered, featureless ocean. I also check the fuel loadout – due to the somewhat rough weather conditions and gusty winds, I prefer to take a lighter fuel load rather than launch with all tanks full.

After all preparations are done, I taxi the plane to the launch catapult and it is attached to the guiding rail. I set the throttle to full afterburner – we are good to go. Windgusts blow the catapult steam all over the deck.

Aircraft in Flightgear allow to customize fuel load, and quite often also the weight distribution of cargo, passengers, or in the case of the F-14, the armamant. All this influences the behaviour the plane will show later in the air, thus this is also an important part of pre-flight preparation. For western fighter jets such as the F-14b, radio navigation is done using the TACAN system. Flightgear has both ‘fixed’ TACAN installations (for instance at airbases) which are part of the scenery, as well as definable TACAN channels to be assigned to AI objects.

In the air

The catapult launches us forward, and will full afterburners roaring our jet is in the air. For a moment the gusty winds shake us hard, but with rolling friction gone the plane accelerates quickly, and as I retract the gear we can climb steeply into the more quiet air above.

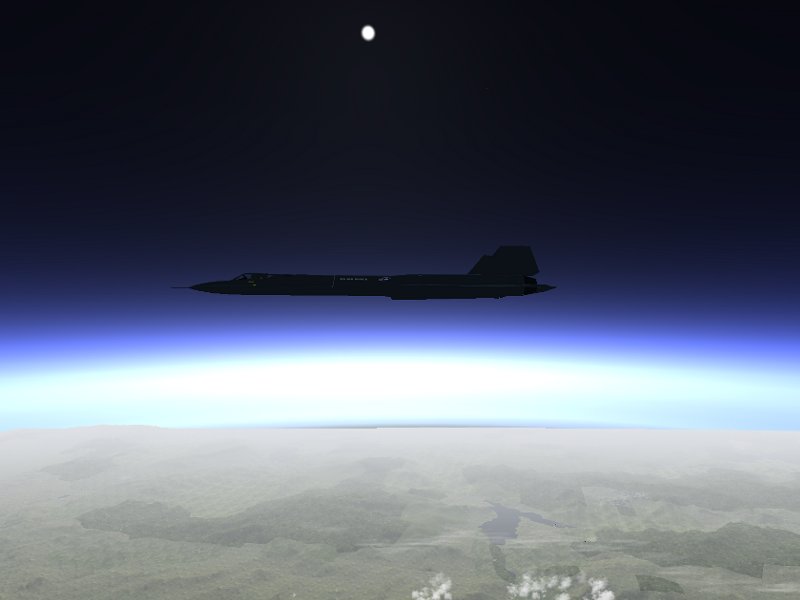

The weather simulation distinguishes between the (usually more gusty) boundary layer winds, and the stronger, but less gusty high altitude winds. The thickness of the boundary layer depends largely on terrain roughness, i.e. it is rather thin – as I pull the plane up, I can leave it quickly.

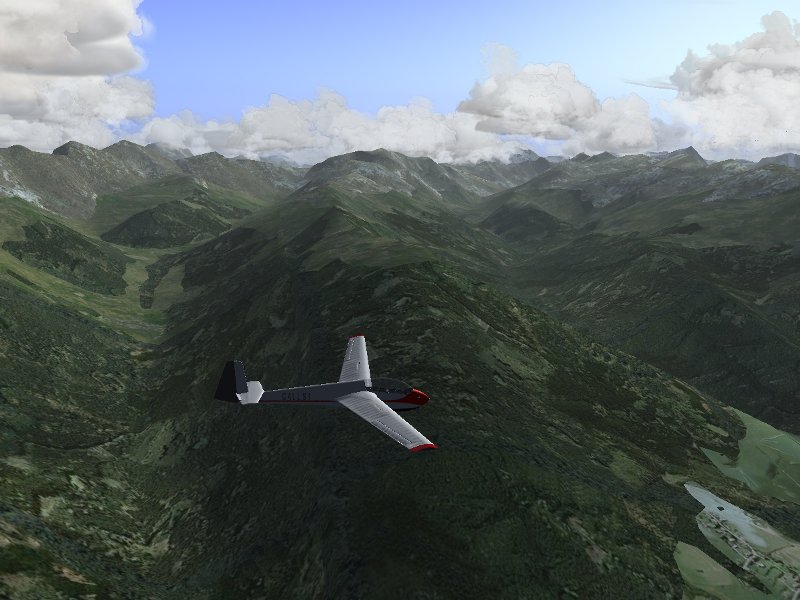

We keep climbing through scattered clouds into a brilliant morning sky.

At 25.000 ft, I level the plane and turn to the planned intercept course. I could use the autopilot for a while, but I enjoy actually flying myself too much.

Many planes in Flightgear have realistic autopilots. In the case of the F-14b, the AP is carefully limited to what functionality its real counterpart can provide – it is a simple system that can level wings, hold an altitude and hold a course, but it cannot by itself follow radio navigation as the more modern systems of other planes do.

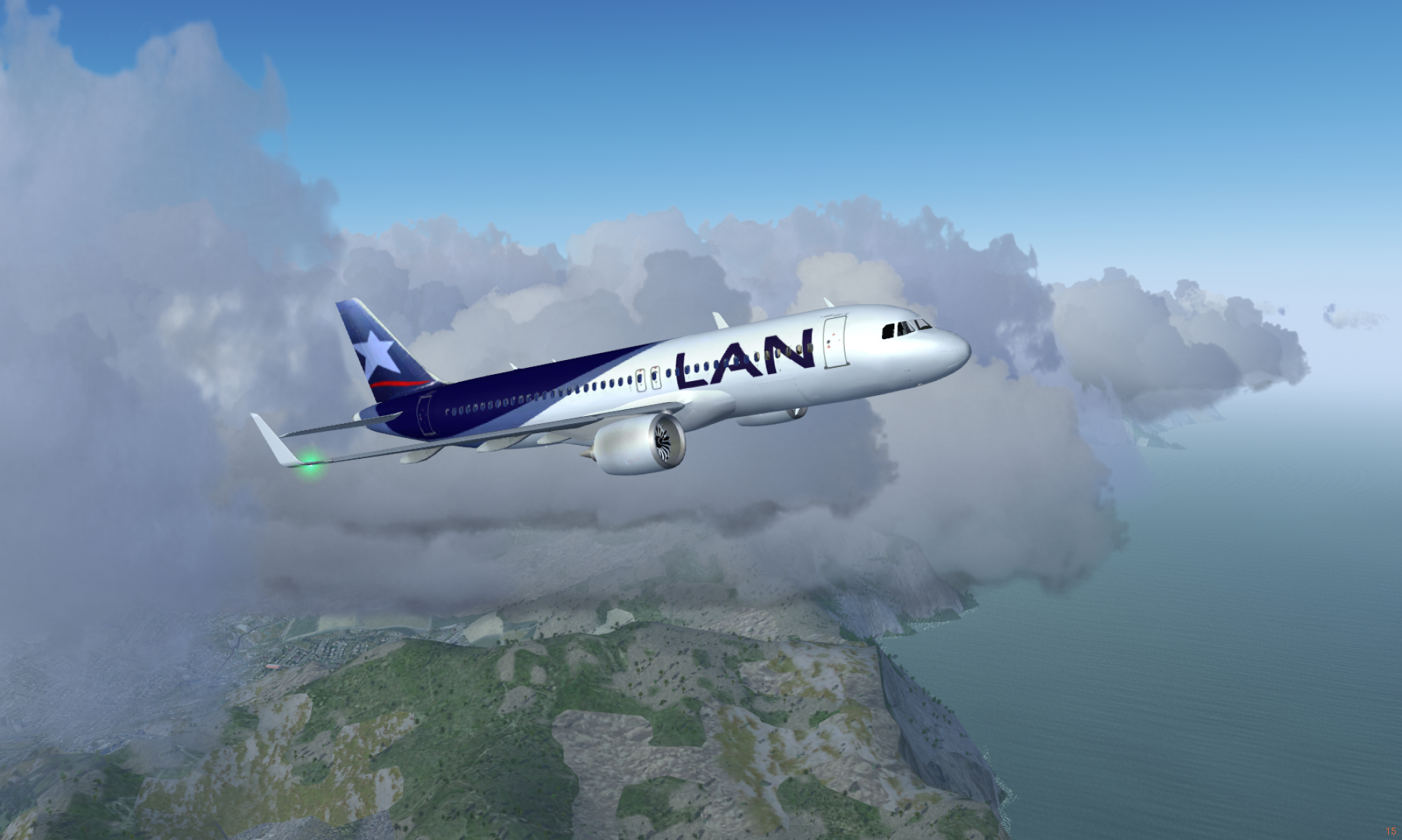

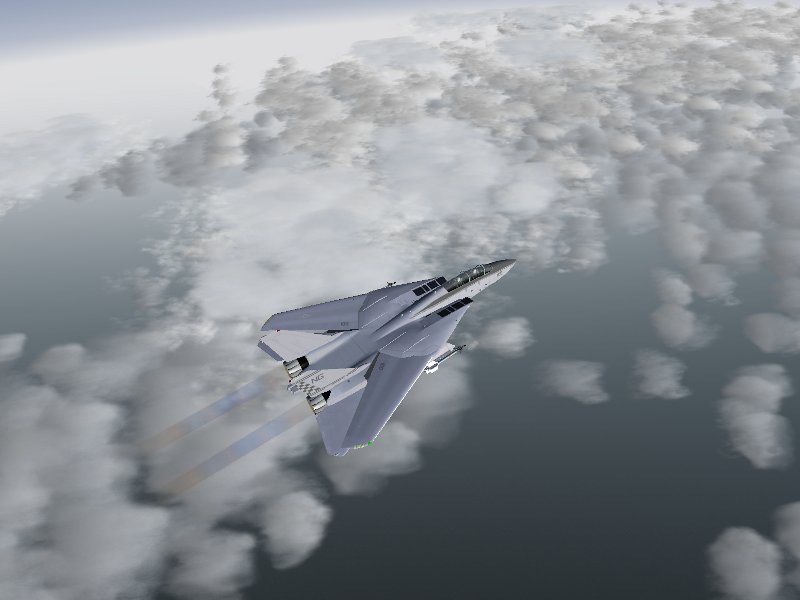

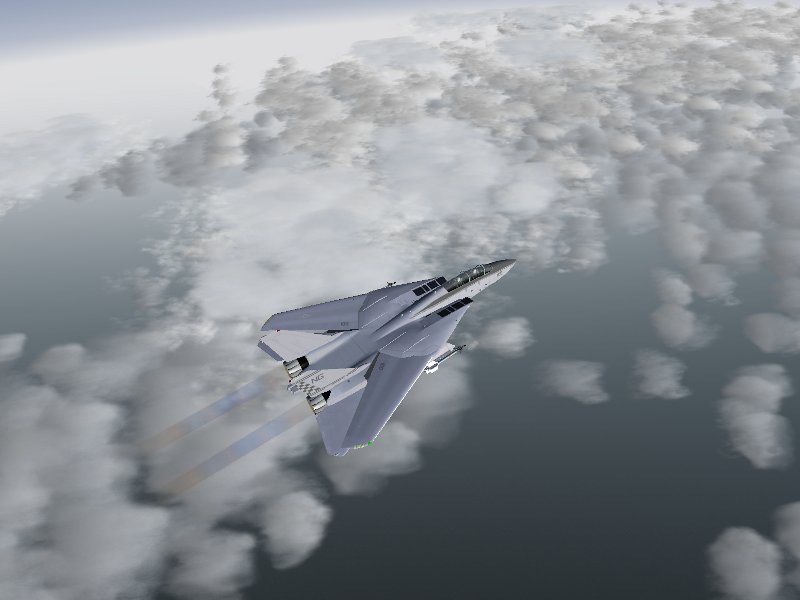

As we go supersonic and race towards the intercept target, the wings automatically fold into their delta configuration to optimize for supersonic flight.

However, today we are in for a disappointment: We do not find the intercept target in time, and racing with full afterburner power, our fuel reserves are quite limited. I decide to abort the chase eventually. To be on the safe side, I ask the Vinson for a tanker.

Tankers could have set up in advance as AI scenario, but Flightgear also has the option to call a tanker for aerial refueling right to your current location – which is what I am using now.

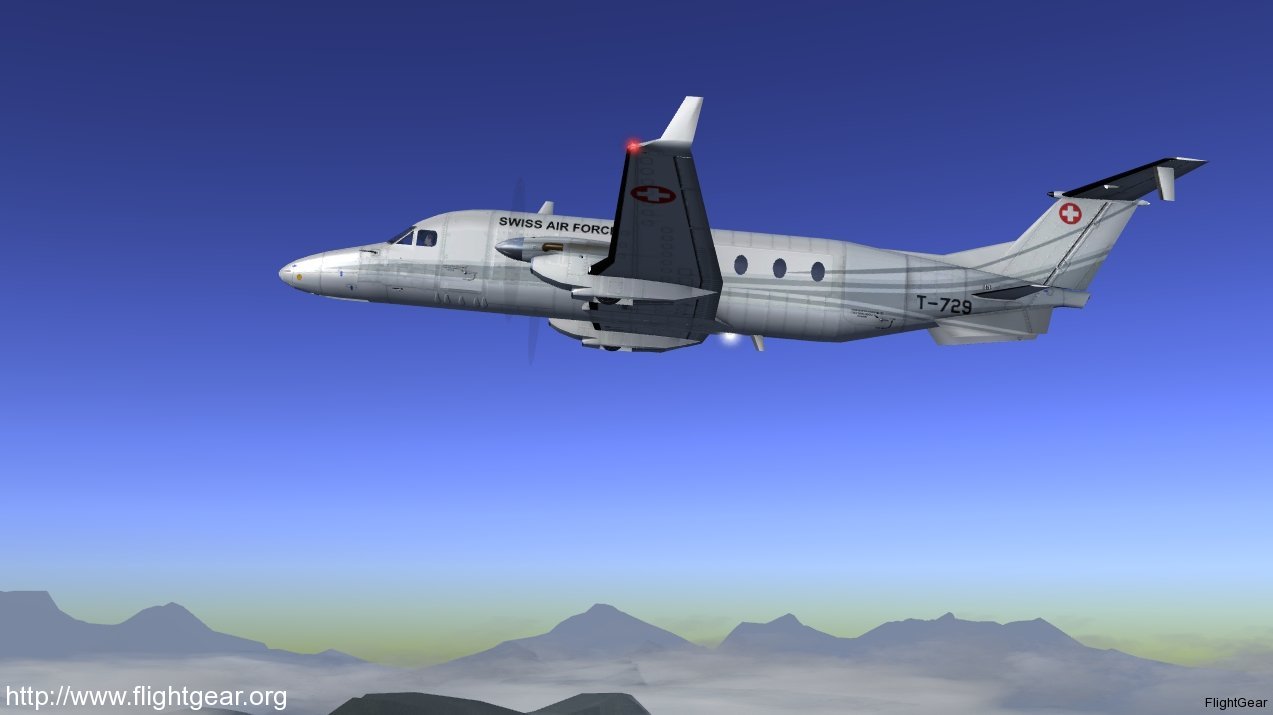

The KA6 used to refuel the F-14b is quite a small plane and difficult to detect visually, but as we ask for a tanker, we get its TACAN channel to guide us into position. However, I decide to track it on the radar instead (as I would for an intercept) and fly the approach by radar.

The F-14b has a fairly radar that is modelled in quite some detail – it has both a scanning and a tracking mode, it provides information about the target heading and groups targets into different types.

Aerial refueling

Getting fuel from a tanker requires some precision flying – the idea is to approach from behind just a bit faster than the tanker, and then to decelerate without dropping altitude just in the right spot. The trick is to gauge accurately how quickly the plane will slow down once the throttle is pulled back – a mistake there will inevitably lead to oscillations around the right position.

With the probe extended, we approach with just above 250 kt into the sweet spot of the KA6.

and finally start receiving fuel so that we can make it back to Vinson

Aerial refueling, both via probe (as demonstrated here) and boom is implemented in Flightgear. Although many aspects are easier than in real life (there is no turbulence induced by the tanker for instance), it is a tricky enough maneuver to master – especially since the AI tankers fly realistic racetrack patterns, i.e. at some point they start to turn!

Back to Vinson

TACAN guides us back to the Vinson. This time, I fly in the subsonic regime. Another 15 minutes later, we start to descend at the position of the Vinson. Here’s the view from the RIO position as we descend towards a cloud later at around 8000 ft.

We overfly the Vinson and its escort group to get into position for an approach.

Then I slow down the plane, extend flaps, the hook and gear and turn into my final approach. Carrier landings, especially in rough winds, are always more of a controlled crash than a proper landing… but TACAN and the Fresnel Lens Optical Landing System are there to help me align properly in difficult conditions.

However, in this case, the unpredictable crosswinds blows me off course.

Weather in Flightgear can change – gust speed and direction may vary on a short timescale, but winds may also change driven by a new weather report in the live weather system or by the dynamics of the offline weather system.

At this point I decide to go around, so I switch afterburners back on and retract the gear, blast by the Vinson and come again for a second try. After contacting the Vinson, the carrier turns into a new recovery course.

AI control allows to modify the behaviour of Ai scenarios runtime. In this case, I direct the Vinson to a new course better suited for my landing while I go around.

Caught by the wire on the second attempt…

Missing the approach the first time is not too uncommon with the carrier – it’s always better to try again and hope that things go better than to try to force the aircraft down onto the deck when thing are not going right. Even when touching the deck, it’s not guaranteed that the wire catches, so one should always be prepared to yank the throttle forward.

Debriefing

We get out of the plane…

This time, the mission was a failure – we did not manage to reach the intercept target as planned. But this is as life goes – sometimes things do not work out as planned, sometimes something goes wrong with the plane, sometimes the weather does unpredictable things. The important thing is to be prepared to abort whatever you’re doing if it’s unsafe, and to react to the conditions. It’s always better to stay on the safe side than to end the day in flames.

Flightgear has the option to randomly fail systems with a certain probability. Had I wanted, I could have set up the simulation in such a way that my altimeter wouldn’t work. In several planes, even quite detailed emergency procedures are supported, such as extracting gear without pressure in the hydraulic system, or engine restart in the air after flameout.

P.S.

Youtube video of Carl Vinson Ops. (Best viewed by clicking “Watch on YouTube” and then going “Full Screen”) Seriously FULL SCREEN and CRANK UP THE VOLUME!!!

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cvbtSG9cy20[/youtube]

Predator drone video footage circling the Carl Vinson …

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PK1uxUZaFBc[/youtube]